His Tombstone reads "George Ash died October 31, 1850, About 95 years

Submitted by: Sheila Kell

The story of George Ash starts before Switzerland county, Indiana was born, and when Kentucky county, Virginia reached to the Great lakes and to the Mississippi river. George is one of to be the first white men to set foot in what is now Switzerland county, Indiana.

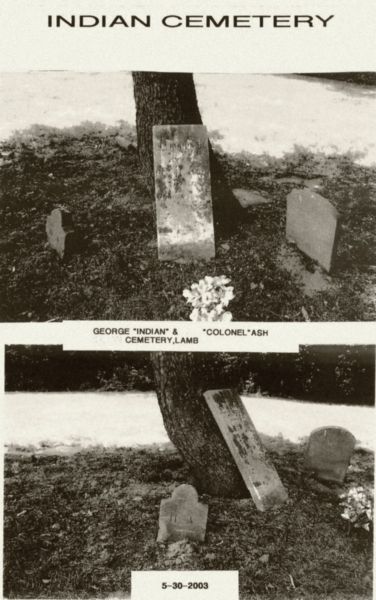

A trip to the old "Ash burying ground" will make a fitting foundation for a record. All the local people called this Cemetery the "Indian" Cemetery and as late as the 1940's it was still known by that according to Betty Breeck Stewart who lived in Lamb when she was growing up!

A short distance below the old Ash home on top of the river banks, nestled beneath old trees, like Indians had just left, I found there, three old freestone tombstones: two leaning together against a tree, and one faced down, overgrown with grass and weeds, indicating only their owners were in the neighborhood, and also badly eroded as to be almost illegible.

The first stone reads:

GEORGE ASH

Died

About 95 years

The second stone reads:

In Memory of Hannah Ash

Who died in the 63rd Year of Her Life

The third stone (face down) was:

ELIZA NORMAN

Daughter of George & Hannah Ash

1817

More Burials in the "Indian" Cemetery

ASH. George C., 1812-1872

Caroline ASH (same stone)

Stratford, Mary, wife of John,

dau. of John & Sarah Miles,

d. Apr.17, 1846, aged 30 y 7 d

That was all I could make out.

Now here is George Ash's family tree as told me some years ago by Nicholas Vineyard Ash, his grandson.

George Ash and wife--Hannah Coombs, their children; George Colonel, Eliza Nornam, (1810-1817)

Eliza Norman was drowned in the backwater behind the old brick house when she was seven years old.

George Colonel Ash--Caroline Munn, their children; were Hannah, George, Betty, Eliza, Henry T., Rachel, James T., Joseph B., Melissa, John, Nicholas Vineyard, Clara Bell, and Nancy Kate.

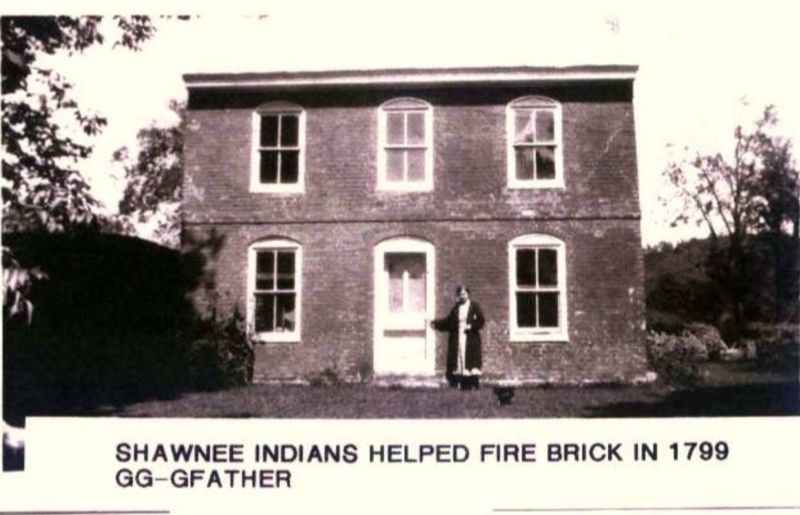

George "Indian" Ash's Home in Lamb, Indiana,

overlooking the Ohio River.

After leaving the old burying ground I stopped to see Capt. Leon Ash, as he is the last of the name, residing here, and asked, "What do you know of your great grandad's experience with the Indians?" He answered "Very little, I tried to find out about him, and father told me to go over to Malin Small's (the historian of Carrolton, who used to come over and chat with the old folks) so I called on the old chap. He told me he had notes on the Ash narrative, intending to put it in book form and intended it for me, but he had loaned the notes to a lady in Ghent. I said, "Get in and I'll drive you up there, I'd like to see them." He answered, "No she will return them, then I'll send them to you." Before I got home he died and those papers could not be found, nor the Ghent lady's name. Mr. Small told me there were no Indians in Kentucky. It was their hunting ground and they warred on all trespassers: "dark and bloody ground.' The headquarters of their confederation was at Chillicothe, Ohio. We were standing in front of the brick house, "Do you know when it was built?" "Yes, about 1798 or 99." After the Indians left a friendly old Chief, who had learned, from the whites the art of making brick, came back and taught great grandad the "How" and helped him make and burn the bricks, and built this house." Tourists tell me they have come down here to see the first brick house in Indiana. Then I asked, "When did he start the Ferry?" He said "I don't know, but the first ferry was a dugout, hollowed from a big tree.

I had read the story of George Ash in a child's History of the United States seventy years ago. It stated only, that the family were all murdered excepting the boy whom the Indians took along with them and raised as an Indian, and used him as a decoy to entice flat boats to land, then they would massacre all on board and plunder the boat. That account never mentioned the father, mother, brothers or little sister.

In their comments they showed George no mercy. It seems History written by contemporaries cannot be depended on for impartial truths. It is always bias by the blur of excitement or emotion and justice can only when sized up by a later Jury.

Biologists tell us every generation through which we pass adds some trait from those who have gone before. Mayhap only a twich, a walk, a voice, but with George Ash, his decendents must have bred back of him without adding anything savage from his Indiana experiences, for the ones I knew were just like the rest of us.

After all my squirmishing around for material; Mrs. Danner, hearing of my troubles, sent me to George Ash's own story copied from "Turners Indian Characters", (actually Turners Traits of Indiana Characters) published in 1829, giving a more complete history of George's wanderings with the Indians than I could have hoped to find by reading a library.

The story being anonymous, can it be possible it is from the lost notes of Malin Small, for which Captain Ash was searching? Did Malin muff the Captain? Captain Ash is Captain of the government steamer "Iroquois", with nothing thin skinned about him. He deals with all sorts. Of course no historian or journalists would betray a confidence, re: George leaving his Indiana wife, therefore the anonymity. And now 108 years after spilling the beans, we feel George didn't look on his marriage as a serious affair.

This first section is from an ancient undated newspaper, which was offered as a prelude to history and was condensed from memory. The Clipping:

"In the year of 1777, John Ash with a number of others settled near Bardstown, Kentucky. They built a Stockade with their log cabins inside, and settled down to their occupations. All was peaceful for three years, but they knew the ways of the Indians and strengthened their stockade and built a tower with loop holes for defense in case of a seige. In the spring of 1780 John Ash with his wife and infant son Henry, made a trip to Clarkesville Kentucky (now Louisville) on a shopping expedition leaving their other children at the stockade.

While they were gone the Indians layed seige. The garrison of settlers stood watch day and night and fought them off for several days. Then the Indians got a fire started against the stockade which soon spread to the buildings. Young George Ash took his little sister and hid themselves in a brushpile alongside the stockade. When the fire reached them, George had to crawl out and pull the little sister out. Then the Indians got them. By this time the buildings were burning fiercely and had to be abandoned, and the garrison were shot as they emerged. The Indians then scalped the dead and after pillaging the ruins, took the children along with them.

Now for George Ash's story copied from "Turners Traits of Indiana Characters" published in 1829. These facts were related to a gentleman in Cincinnati, Ohio, by George Ash himself.

"My father, John Ash, was one of the earliest settlers in Kentucky, settling in Bardstown in Nelson county. In the month of March 1780 when I was about 10 years old, we were attacked by the Shawnee Indians, part of the family was killed, the rest were taken prisoners. We were separated from each other, and excepting a younger sister, who was taken by the same party that had me in possession, I saw none of my family for seventeen (17) years. My sister was small and they carried her two or three days but she cried and gave them trouble, so they tomahawked and scalped her and left her laying on the ground. After this, I was transferred from one family to another and treated harshly and called "White dog" till at length I was domesticated in a family and considered a member of it. After this my treatment was like that of the other children.

The Shawnee's lived at this time, on the Big Miami, about twenty miles above Dayton. Here we continued until General Clark came out and burned our villiage. We then removed to St. Mary's and continued for about two years. After this we removed to Ft. Wayne on the Maumee. Here we were attacked by General Harmer, when we removed to the Auglaise river and continued there some years. While there General St. Claire came out against us. Eight hundred and fifty (850) warriors went out to meet him and on their way they were joined by fifty (50) Kickapoos. The two armies met about two hours before sunset. When the Indians were within about a half mile of St. Claire the spies came running back to inform us and we stopped. We concluded to encamp. "It was too late" they said "to begin the play." General Blue Jacket was our commander. After dark he called all the chiefs around him to listen to what he had to say. "Our Fathers" said he, "used to fight as we do now; our tribes used to fight, and they would trust their own strength and their numbers, but in this conflict we have no such reliance, our powers and our numbers bear no comparison to those of the enemy and we can do nothing unless assisted by the Great Father. I pray now, continued Blue Jacket (raising his eyes to heaven) and we shall take it as a token of good and we shall conquer!"

About an hour before the orders were given for every man to be ready to march, on examination, we found that three fires or camps consisting of fifty (50) Pottawattomies, had deserted us. We marched until we got in sight of the fires of St. Claire, then General Blue Jacket began to talk and sing. The fight commenced and continued for an hour, when the Indians retreated. As they were leaving the ground a chief by the name of Black Fish ran in among them and in a voice of thunder said, "What are you doing? Where are you going? Who has given orders to retreat?" This called a halt and he proceeded in a strain of most impassioned elegance to exort them to courage and concluded by saying that his determination was to conquer or to die. The attack was most impetus and the carnage for a few minutes was most shocking. Many of the Indians threw away their guns, leaped in among the Americans and did the butchery with tomahawks. In a few minutes the Americans gave way, the Indians took possession of the camp and the artillery, spiked the guns, and parties of Indians followed the retreating armies many miles. Eleven hundred (1100) Americans were left dead on the battlefield. The number of Indians killed amounted to Thiry Five (35).

"In this battle," says Ash, "a ball passed through the back of my neck and the Indians carred me from the field. I had a brother killed with the American Army. After this battle I started with eight other Indians on an embassy to the Creek Nation. Our object was to renew the friendly relations between that nation and our tribe. While we were away our tribe had a battle with the whites near Ft. Hamilton. The American army was commanded (I think) by General Bradly. After our return General Wayne came out against us with eight thousand (8,000) men. We sent runners to all nations to collect warriors together and soon an army of one thousand five hundred (1500) was in the field. We marched out to meet Wayne, who was then at Ft. Recovery. We took one of Wayne's spies in our march, a Chcasaw. He was taken to the Indian army that he might give some account of Wayne's movements, but the Indians were so enraged at him they fell upon him, in the midst of his narrative, and killed him. Our army was then in great need of provisions. The Chippesaw Indians cut up the body of the Chicasaw, roasted and ate it.

Near Ft. Recovery we met a party of the American army and fought them. Wayne marched on the towns and only three hundred (300) warriors could be mustered to meet him. We fought Wayne two battles. The Indians were conquered and the war ended."

Ash had now been with the Indians seventeen (17) years. He had long identified himself with them, spoke their language perfectly, (and almost forgot his own) had adopted their dress and all their modes of life. His right ear was fixed in a peculiar way for the purpose of wearing jewels. The edge of the ear about a third of an inch deep is cut off excepting at the end where the ear joins the head. This ring hangs down on the face and serves as a kind of loop. The parting gristle of the nose is perforated; there is likewise a hole in his left ear. He was painted and wore a hundred dollars worth of silver ornaments. In his nose, he wore three(3) silver crosses, seven(7) half moons, valued from five to six hundred dollars.

"After peace," continues Ash, "I told the Indians I wanted to go to the white settlements to see if any of my family were living. They at first made objections but finally concented and in full Indian dress, with a good horse, gun, and a good hunting dog, I started for Ft. Pitt.

Having traveled fourteen(14) days in the wilderness, I arrived at the place of my destination. I there found a brother and learned that my father was still living in Kentucky. After staying for some time at Ft. Pitt, I was employed by a gentleman as a guide through the wilderness to Detroit. When we arrived in the neighborhood of Detroit. I told my employer that he might go on and I would spend the winter among the Indians with my wife, for I had taken a wife among the Indians. He called for me in the spring and we returned to Ft. Pitt together. I, there sold my horse and proceeded down the river in a boat, with the intention of visiting my father. I arrived at his house in the night, called him up and requested entertainment for the night. He denied such a request to no man, but he evidently was not pleased with my appearance, for I was still in Indian costume and could speak but a few words of English. He paid but little attention and I asked him some questions about the family. I asked him is he had not a son George many years ago taken by the Indians. He replied that his son was killed in St. Claire's defeat. I stood up and said, "That son now stands before you." He looked at me with searching scrutiny and commenced pacing the room. "Would you know your brother Henry if you were to see him?"

He asked. I said "No, for he was a mere infant when I was taken away,"

My father rode several miles to bring my brother, Henry. My father had become wealthy, possessing negros and horses in abundance. My mother had died and my father had married a second wife, who was not backward in letting me know that there was no place for me.

I started again for the Indian country, across the Ohio river and pitched my camp on the spot where my house now stands on the banks of the Ohio exactly opposite the mouth of the Kentucky river. After hunting for some time, I determined to make another visit to my red brethern, and a friend gave me a horse to ride. I found the Indians preparing a deputation for their Great Father, the President, and nothing would do but that I make one of the party. With a number of Cheifs, I set out for Philadelphia. After visiting the President, I returned to my old camp where I now live, across the Ohio river, from the mouth of the Kentucky river.

As a compensation for my services on this mission the Indians granted me a tract of land opposite the mouth of the Kentucky river, four miles in length and one mile back. When the territory was seated to the United States, the Indians neglected to reserve my grant. I had cultivated some part of my land and it was worth more than the government price. It was offered for sale and I petitioned congress to secure for me what was in fact my own. They denied me the request, but permitted me to purchase as much as I could at the government price.

I considered myself rich in lands, but poor in cash and my domain was reduced to about 200 acres. On this I have lived ever since." (George's story tallies up fairly well with Gen. St. Claire's report which is here abbreviated.)

In the battle on the Auglaise, St. Claire had all told 1400 men, less 60 deserters. He estimated the Indians at 1200, less 50 deserters. Most of his men were raw recruits. He had camped on a knoll surrounded by dense forest and bushes, with a creek on his right. The Indians surrounded them and opened fire from behind the trees on all sides. St. Claire quickly formed his regulars and ordered a bayonet charge. The Indians gave way but the slaughter of his regulars was frightful. The Indians came back and his raw recruits stampeded to Ft. Jefferson, 29 miles away, most of them reaching there that evening. The Indians followed them four miles. St. Claires loss was 632 men.

About one hundred women (wives and mothers of the recruits) were in the camp. In the disasterous retreat, very few of them ever reached Ft. Jefferson. Three months later reinforcements arrived and a hundred men were sent to the battlefiend to salvage what was abandoned. They found the bodied of the women horribly mutilated, limbs torn off, some with stakes driven through their bodies into the ground, also wounded soldiers with their eyes gouged out and tortured to death. At St. Claires report to our war department in 1791.

The French settlers always got along peacefully with the Indians so when the British concluded to boost the French out, the Indians sided with the French, and never got over it.

The Indians complained, when we want some bark to keep out the rain the Americans went "Yeow!" while the French said, "Help yourself." The Indians had traded their lands for mess of pottage, and wanted it back. The pottage was principally whiskey and Jim cracks. These lands included Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Kentucky, several thousand square miles of the richest spot on earth. There were about 2500 braves in the confederation. It is estimated there were less than half a million Indians in all of North America at that time. There warfare was like Don Quixote charging the windmill, and resulted in their having to sign the "Treaty of Greenville" in 1795, compelling them to stay west of the Indian Boundary; a line drawn opposite the mouth of the Kentucky river, through Lamb (Ind.) to a point on the Ohio state line at Uniontown, Indiana.

This ended the Indian warfare so far as Switzerland County was concerned, but the settlers were always jittery with Logan (Lo) so close. A dozen Shawnees attacked the settlement at Pigeon Roost, only 40 miles west and massacred and scalped three men, five women and sixteen children.

But poor Lo had a side to his story too, for who would not feel for Logan. The cruelty of Cresap in the murder of his wife and children. With the tears streaming, Logan said, "Not a drop of my blood courses through the veins of another who will mourn for Logan now? Not one!" The cowardly murder of Cornstalk, his son, who, unarmed volunteered as hostage for fulfillment of the treaty; he answered a knock by opening the door of his unguarded prison and received seven bullets through his body. His son was also slain by order of the Post Commandant. The settlers seemed to hold open season for Indians.

Included in Rick Allen's package of George Ash memorabilia was a description of "Injun George" before he returned to the white man's world-a description that appeared in the 1829 "Turner's Traits of Indian Characters " and that supported George Ash's statement about being truly Shawnee.

"He (Ash) had adopted their dress and all their modes of life. His right ear was fixed in a peculiar was for the purpose of wearing of jewels... He was painted and wore a hundred dollars worth of silver ornaments. In his nose, he wore three silver crosses and seven half moons, valued from five to six hundred dollars."

After the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, however, Indian warfare in Switzerland County came to a close, and George Ash concluded that he would have an easier time surviving as a white than as a Shawnee.

He worked as a guide and interpreter for a while, and he even found his father, John Ash, alive and well in Kentucky. John would have nothing to do with his long lost son, however, and George eventually settled on land given to him by the Shawnees near what is now Lamb. Although he lost much of that land in a dispute with the government, he and his Native American friends built a house of hand-made bricks on what property he was able to retain-a house that still stands over-looking the Ohio River at the western edge of Switzerland County.

According to a note by William Patton in the Revelle Enterprise of December 9th, 1937. "It was easy for George to revert to the white man's ways again, and he became an exemplary, public spitited citizen. He joined the Methodist Church and donated the ground for a new Methodist Church at Union (now Lamb).

George Ash became a successful ferryman and ended up living more than half a century after the Treaty of Greenville, dying at the age of 95. He passed his trade down through generation of his family, and his great-grandson, Leon Ash, became a well known riverboat captain on the Ohio.

Rick Allen's story came to a close with words that suggested the difficulties George Ash experienced as he made his transition from warrior to ferryboat operator:

"And so, here I am. Trying to live out my days among you as a white man. It's not easy. Few can forget what happened during those early years. Fewer Still can forgive. Just last week, a passenger on my ferry tried to kill me with own boat hook. His wife recognized me as the man who, years ago, had to take a piece of her scalp.

I did not choose the life I have been given, It was chosen for me. There is nothing I can do to change the past. But the fighting has ceased, and you have nothing to fear from me now. I am but an old man who wishes to end his days in peace. So judge my words as you see fit, for now you have heard ther truth about "Injun George".

Now for a society column of a century or so ago, in which George had a part.

(Nancy Kate, his grandaughter on the telephone)

After his rebuff by his stepmother at Bardstown, George took a notion that a white wife would suit him better than that "She Bear" whom he had left behind. So he shined up his silverware, brushed up his coonskins and started out to find one. For a while he didn't have much luck. Old residenters had told me, he was far from handsome, and he was beginning to despair. In desparation he decided to tackle the first girl that came along. Directly two damsels moved into sight. He stopped them and stated his case to the one that took his fancy and was accepted. It was Hannah Coombs.

George returned from the visit to his father, to Lamb, (Indiana) to what he thought was his land and built a large log cabin that stood until thirty or forty years ago. About 1897. Some thought his deed from the Shawnees and Delawares should have been allowed to stand, but the congressional committee had authority to grant it. Whatever their sympathy, (for tho I've understood they sneered at him) Congress alone had the power to legislate, and George had no pull there. However the committee recommended that he be allowed to buy the 640 acres on which he had made improvements, and pay for it in the usual way, which was, "NO-MUN NO DIRT".

He

appealed to congress in 1802.

National Archives

Records of the Office of the Secretary of War,

Letters Sent, Indian Affairs, Vol. A.

Conference

held with the Delaware and Shawanoe Deputation, February 5-10, 1802.

pp. 149-157.

153

from both Towns the Delaware at White river and the O Hana town.

Brother,

Our wishes towards our great Friend Francis Duchouquet we hope will meet

yours, the man has lived

& traded along time in our towns and we never know any bad

things of him. Our intention is to give him one mile square of land

where he now

has a House in our Country & as it is the will of the Nation,

we hope you will

sign a Deed that no one may ever disturb him and if you think him of

service to us we would rather

hav[e] him than any other person-

Brother,

The other Interpreter is a man we raised from a Child and look on him as one of ourselves, we therefore with to give him Four miles down the river and one mile up the land, his name is George Ash and the plac[e] we meane for him is at the mouth of Kentuckey on the Indian boundary line[.]

His appeal to congress in 1802 got the above answer of "NO MUN NO DIRT" in 1807. According to his story he had only enough money to buy 200 acres. Nick (Nicholas Ash-his grandson) told me (Nancy Kate-Nicks sister) it was 375 acres.

George was no farmer, he had seen how the Indiana Squaws had scratched in a little corn to supplement food supplies through the winter, when the hunt was slim, so he did likewise and soon ran behind and had to sell off the bulk of his land at times. (114 acres to William Lamb, now the Lamb farm).

The ferry franchise became very valuable to his dependants and his decendants dependence for 125 years. He prospered because his was the best landing for a ferry.

Long after the "Treaty of Greenville" the Indians would come back in force, for a friendly visit with George. They would camp in the big beech grove behind the Lamb church lot, where they would make merry; sing, dance and eat.

On one such trip, Foxtail was tried for stealing a blanket. He was found guilty and sentenced to death, they gave him several days to arrainge his affairs.

He willed his pony, saddle, bridle, earrings and other acoutrements to George Ash. The time arrived for his execution . He took his place in the center of a circle of about fifty (50) Braves. Everything ready a brave left the circle, approaching him with upraised tomahawk to strike the fatal blow, let the weapon drop behind his heels and fanned the culprit with his empty hand. This proceeded around the circle to the last Brave, who possibly meant business as he raised his tomahawk to strike, a Brave behind him grabbed the tomahawk and threw it to the ground, took Foxtail by the arm and led him to his pony and acoutrements and pointed to the forest. Foxtail understoood, mounted his pony and rode away. "Grandpap was greatly put out and dissapointed over the loss of his inheritance," said Nancy Kate.

A man and his family were crossing the river by George Ash's ferry to Kentucky to visit relatives. Suddenly the wife screamed "This is the man who scalped me." The husband grabbed a boat hook and rushed at George, who jumped overboard and swam to shore below the mouth of the Kentucky river, and laid low until his passengers had gone on their way.

I've always understood scalping was a fatal operation or was it a tomahawk that made it so? An Indian said they used a tomahawk because the victims wouldn't hold still.

I can imagine George pondering, "Why should I kill this poor woman who has done me no harm." So her took her small topknot and spared her the tomahawk, showing he still had within him a spark of mercy.

The Indians probably twitted him as being a sissy with no scalps in his belt. He said, "I just couldn't take much part in their War Parties"

It was easy for George to revert to the white mans ways again, and he became an examplary, public spitited citizen. He joined the Methodist Church and donated the ground for a new Methodist Church at Union (now Lamb).

I would like to note here; the fate of this Methodist Espicopal Church: the Membership dwindled to zero from causes known to those who have gone before. They, (like the English Sparrow and the Martin Box, with none to say nay), the Baptists moved in, and have been in possession ever since, a thrifty organization. Reverand Alan Wiley, a pioneer Methodist Minister held services in George's log cabin.

After this late day we look with lieniency on George as a victim of circumstance, with some raw deals attached, and know you will give him belated justice.

From Betty Breeck Stewart,

The Story as the Family Told It

When George was granted land by the Shawnee Chief and left the tribe, with the Chief's blessing. The Chief did request George do one thing. That George give his word, to have his Indian "brothers" visit with him in Lamb Periodically. He asked that George visit the tribe once in a while. With this understood between them, and George agreeing, he left his "second family," with full promise to return to the Indian Village and the Cheif for short visits. When the Indians came to visit George, in Lamb, they would camp out in what is now the Union Baptist Church Yard.

The Land the Shawnee granted George was thought to be from above the Allen Netherland Farm where the old "Indian Boundary Line" was down to what is now Doe Run on this side of Brooksburg. The Government got into the "giving and deeding," of this land. They told George the Indians didn't own the land, the Government did! If George wanted the land he would have to pay for it. George decided to buy as much as he could afford. It was thought to be near three hunderd (300) acres, more or less. Itwas rumored to cost him about One hundred twenty five ($125.00) dollars. Which averages out to about .41 cents per acre. In this acreage, George donated land to build a Methodist Church. The Methodist Church was either bought out by the Baptists or taken over by them. The Union Baptist Church was established in 1841 and still stands today. Both the Community of Lamb and the Church are active today. The members have preserved the Church well over the years. All of the Leslie & Inez Breeck children attended and six (six) out of eight (8) children were baptized in that Church.

George soon began "running" a homemade, dugout canoe across the river from Lamb to Port William Kentucky (now Carrollton). It was on one of those trips that George met his future wife, Hannah Coombs. He saw her and told his helper, he was going to marry her. He did mary her within a few months of that "prophecy"! Hannah was from Nelson County, Bardstown, Kentucky. They were married on or about December 31, 1799.

George and his "acquired brothers" had by then, finished building the brick house in Lamb. George and his bride moved in. It was time to start a family and a "ferry boat business." The family would not commence for several years, however the boat business flourished under George's hard work and direction. The year was 1816. George seen began using a horse and wheel. The Lamb-Carrollton Ferry Boat was in business. The Ash owned business would run for one hundred six (106) years until the year, 1922. It wasn't too long before Colonel George became old enough and interested in helping run the business. In 1841 Colonel had his first son, George W. and thereafter went to have six (6) more sons. Several of whom worked the boat business. Joe B., and his bachelor brothers, John Thomas (Stormy), Ol (Timothy), and Nick seemed to take the most interest. In fact, Joe B. took over the business from Colonel prior to Colonel's death in 1875. It wasn't long before "The Little Minnie" was up and running in 1884-1885. Next came "The Leon", which was named after Joe B's only living child and son, Leon, in 1895-1896. Then came "The Mary Jo" named after Joe B's wife, Mary Jean and himself, in about 1919 Copies of photos of these boats where supplied by: Captain Bernard L. Breeck, Great Grandson of Colonel George, Captain Steve Huffman, who also supplied photos of boats running on Lake Webster, North Webster, Indiana. Steve also now lives on formerly owned Ash Land. Also Sheila Kell who is a cousin through Caroline Munn Ash-Maryette Beebe Munn Stewart. She entrusted her tintypes of "The Little Minnie" and a photo of Nancy Kate Ash Breeck, when she was about fifteen⁄sixteen (15⁄16) years of age. Dennis Banta supplied photos of Joseph⁄Mayme Breeck, his Great Grandfather and his Grandmother and his parents, Nelson and Bessie Banta. (will be including pictures later)

So many thanks, to all who contributed in any way to this Ash-Breeck History.

It was thought George "Indian" was b. 1750-1755. George "Indian" d. 10-31-1850, in Lamb. He was close to ninety-five (95). No one is sure of his accurate age. Hannah Coombs Ash was b. 1768 and d. 1837, in Lamb, IN.

Colonel George and Caroline Munn Ash, did document most of the Ash births and some of the death dates in the Ash Family Bible, especially those pertaining to their immediate family. Which I copied from in 1964, when Mrs. Alma Ash was living in Lamb.

This is the story of George "Indian" Ash, as it was "handed down" through our family. How much is non-fiction, how much is fiction? Only Great Grandpa, Colonel George, Great-Great Grandpap, George "Indian", Great-Great-Great Grandpa John Ash would know for sure.

When you think of "Indian" Ash's, married life, which commenced in about 1799, a few years prior to Indiana becoming a State in 1816. Also, before Madison was established in 1809. They were real pioneers of Switzerland County, Indiana. Their accomplishments, during Geo. Indian's and Colonel George's lifetimes, along with those of their wives and families, warrants this "family account," to continue on for the coming Ash-Breeck descendents.

There is documentation in the Switzerland County Historical Society, Vevay, Indiana, to verify much of what is said herein.

Many of the name spellings herein are taken from John Ash's Last Will and Testament and from George "Indian' Ash's Last Will and Testament. George "Indian" always referred to his son, as "Colonel" George so I would assume that was his legal name. Also many spellings of names taken from the Ash Family Bible. I added the nicknames, as they were referred to by the family. Nicknames were not in the Ash Family Bible. Betty Breeck, states that Evan Ash who lived next to George in Lamb, was a son of George & his Indian wife, She Bear she states "I know he was".

This is sort of pieced together as there were a number of different stories included from different sources. Most of the printed History of Switzerland County has very little mention of George. I feel that because of his life with the Indians many who lived through the Indian wars still resented him although it was not by his choice that he was captured he made the best of it and tried to stay connected to the Indians after he came back to his heritage as a white man. It must have been difficult for all concerned. It is believed that he had children or at least one child with his Indian wife She Bear and we are still trying to prove this.