PIONEER LIFE ON DEER CREEK

From the records of Bonita Welch, Jenning County Researcher descendant of the William Vawter Family.

North Vernon Plain Dealer---November 15, 1923

My grandfather, William Vawter, entered 640 acres of land from the Government in 1818 and this became what is now known as Deer Creek neighborhood. My father was Armand F. Feagler, a Baptist preacher. The families of the neighborhood in my boyhood days were the Fairgoulds, Pettses, Abercrombes, Wagners, Clarkstons, McCaulous, Levetts, Fitzgivenses, Bears, Richardsons, Midcapps, Kings and others whose names I cannot recall. The cabins and clearings were all on the hills as the flats--in what is now the Oakdale neighborhood--were covered with water all during the summer months and if one attempted to ride a horse through this flat land the animal would sink to its knees. These swampy flats caused chills and fever, the principal ailments of the time, so for this reason the people cleared the hillsides and built their cabins of the hilltops. My uncle, Miles McCaulou, who lived about one half mile from Deer Creek on Stribbling's Branch, had the largest clearing. He had ten acres cleared while most all of his neighbors had a clearing of only one and one half or two acres. The uncleared land was covered with heavy timber, there was no underbrush and when going through the woods one could see for a mile if the ground were level.

There was plenty of wild game and for our meat we had chiefly wild turkeys and deer. I have seen as many as five hundred wild turkeys in a flock and the deer ran wild all over the country. I remember seeing twelve deer in a herd when I was about ten years old. We could have turkey and venison for the table whenever we wanted to go out and get them. Hogs ran wild in the woods. They were no wild hogs but they ran wild and belonged to anyone who wished to go out and shoot them. Hogs were not used much for food, however, as the people did not like pork. The meat from the hogs in the wild state was very fat and when dressed and cut up for food it melted away into grease if it were left standing very long. I presume it was because the hogs were forced to feed entirely upon beech mast. It seems strange to me now when I remember that we raised only a few chickens.

Vernon was the town in my boyhood but we went there only for a few things such as salt, hoes, shovels and rakes. Everything we needed was raised or made in the neighborhood. We planted corn by using an iron prod or a hoe to dig the hole for the seed and then we cultivated it with a hoe. It would have been impossible to cultivate it in any other way on account of the stumps. We took the corn to Andrew's mill, the ruins of which can still be seen near the railroad bridge, east of North Vernon on the banks of the Muscatatuck. We would put a peck or a half bushel in each end of a sack, threw the sack across a horse and sit on it as we journeyed to the mill. Some people grit the corn with a tin with holes punched in it, then sieved it out and baked it that way. It was a great deal better bread than the bread now-a-days.

When we went to the mill, each fellow had to take turn in getting his corn ground and the miller kept out part of the meal as his pay. I remember when I was about seven years old my father sent me to the mill and when I returned I had such a small amount of meal that he asked me if I had spilled any of it on the way. When I told him that was all the miller gave me he took hold of the bridle and led the horse back to the mill over the road that I had traveled. When we reached the mill the miller told my father that I must have spilled the meal, so the miller filled up my sack. Besides bread the rest of our food we picked up in the country. We raised potatoes, corn and cabbage in the clearing. We made maple sugar in a big sugar camp and we melted the sugar when we wanted molasses.

The women made everything that was needed in the house. They spun the flax and wool for clothing and bedding. They cooked the grease from the wild hogs and worked it up with wood ashes into soap. Some of it we called soft soap; some of it they made hard and could cut it in slices. Candles were used for lighting and these also were made by the women. They would make heavy woolen strings and would dip twelve of them at a time into tallow. They would dip them and let them harden until this process had been repeated about thirty times when they were ready for use. They usually made enough at one time to do for a year. It took about two days to make a batch of candles and then they were put away in boxes until they were needed for use.

My uncle, John Stott who lived where the Zoar School now stands, had a tan yard. All the people of the neighborhood brought their hides to him to be tanned. He had large vats dug in the ground, each vat being four feet deep. He would put a layer of hides in the vat, cover them with a layer of ground up oak bark, then another layer of hides and another layer of bark and so on until the vat was filled. He would then fill the vat with water and let the hides stand for six months. At the end of this time the hides were taken from the vats and the hair scraped off. Then he would put the hides back in the vats in the same manner as before, a layer of hides and a layer of oak bark and cover with water. They were left in the vats for another six months and then were taken out and dressed. The dressing process consisted in stretching the hide over a log and rubbing with an iron rubbing utensil. When the hides were dressed each man took home the hides that belonged to him and the leather was made into shoes. My father made all our shoes but sometimes a cobbler would visit the neighborhood and make shoes for other families. The soles were made out of the heavy leather and the uppers out of the lighter skins. The shoes would not leak water. It was a common thing in those days to cut down a big oak tree that today would be worth fifty dollars just to get the bark for tanning. The tree was left lying as it fell until it decayed. There was plenty of dead wood for fuel and as the main object was to get the land cleared, every big tree that was cut down was a step in the right direction.

The school houses of my day were log houses the same as the cabin homes. My schooling consisted of three months at the Zoar School when I was nine years old. The school house that I attended had glass windows but there were some of an earlier date that had tanned fawn skins, which were thin and transparent, atretched over the openings for windows. I studied, reading, writing and spelling. This completed my education for the time but I attended one term at Deer Creek School when a young man after the war to study mathematics.

I was always told that there were lots of Indians on the Muscatatuck north of us and over on Sand Creek, near what is now Butlerville, but I never saw them. There was one tepee, however, at the mouth of Stribbling's Branch and I went over there once to see them. The tepee was made of hickory bark, curled from the sun, and fitted together so as to turn the rain. I remember that the day that I visited this tepee the Indians were eating black snakes.

When the building of the O. & M. Railroad was started in 1857, a town had sprung up where Simmons brick yard now stands. The town was called Clifty. There were nine dwelling houses, a ten room frame hotel, a store and a blacksmith shop. The men who were employed on the consturction of the railroad were boarded at the houses and the hotel in Clifty. While this railroad was in process of construction, I was employed hauling dirt for the fill. J. B. Millan was walking boss, dump boss and paymaster. I hauled dirt for the fill between the two bridges and above the bridges. I got fifty cents per week and boarded myself. Norton and Black were the contractors.

In my young days we had not much reading matter but what we had was treasured highly. Bunyon's Pilgrim's Progress, Miss Shipton's Prophecies and a few other books the name of which I cannot remember were volumes of the day and they were loaned around the neighborhood so that everyone had a chance to read them. They were handled with the greatest care and were never allowed to reach the hands of children who might mutilate or destroy them. I remember distinctly how thrilling was the book of Miss Shipman's prophecies for she told that at some future time vehicles would run with horses and machines would be flying through the air. A few of us have lived to see her prophecies come true.

We had our fun in the old days, too, when we would gather for dances on the puncheon floors and make merry with the square dance and quadrille with the fiddle for our orchestra.

The present fish and game laws and the Fish and Game Protective Society of today remind me of the time when fish were plentiful in the streams. I am afraid no one will believe me when I say I have seen fish so thick on the riffles in the Muscatatuck that one could walk across the stream on them. We used to set traps and catch them and they furnished part of our food. I remember, when I was nearly grown, of seeing fishing parties from what we then called Germany and what is now the St. Ann neighborhood. Every fall thses people would come to the creek in crowds with wagons loaded with empty tubs and barrels and seine for fish. One little dip and they would get all the fish that three or four men could pull out with the seine. There were women in the party, always, and they would scale and clean the fish and throw them into the barrels in the wagons.The fish were salted and kept for winter food. These fishing parties were always joyous affairs.

When father made trips to Vernon he always took me with him. I would ride behind him on the horse and whenever we stopped I would hold the horse while father did the talking. We always came across from Deer Creek and traveled up along the branch that runs back of what is now known as the Verbarg place; we went on through the woods until we struck the State Road near what is now the Fair Ground. The northern part of what is now the City of North Vernon was wooded area composed mostly of poplar, walnut and beech trees; a little to the west the woods was composed mostly of white oak. The biggest poplar tree I ever saw was standing on the spot now occupied by the Philbarg Theatre. It was six or seven feet in diameter. There was another road that led from the Deer Creek neighborhood and came in over what is now Irish Hill, then down through what was later the Babb and Tate farms, crossed the railroad and struck the State Road north of what is now the Overmyer place.

My first memory of North Vernon is when there was but one house, where the North Vernon Lumber Mills now stand. The house was occupied by a family named Padgett. What is now the center of town was a low swamp almost a pond. The first real settlement of the town was made by families named Houppert and Schubert, who built some houses and started a coopershop on the State Road, in the place that we now call near the Red Bridge. As North Vernon was building, the houses of the little village of Clifty disappeared one by one; most of them being destroyed by fire casued probably by sparks from the engines on the new road.

When the Civil War started, we young men of Deer Creek volunteered and I was gone four years fighting for the Union. When I returned I found things had changed a great deal and some frame stores and other buildings had been erected in North Vernon.

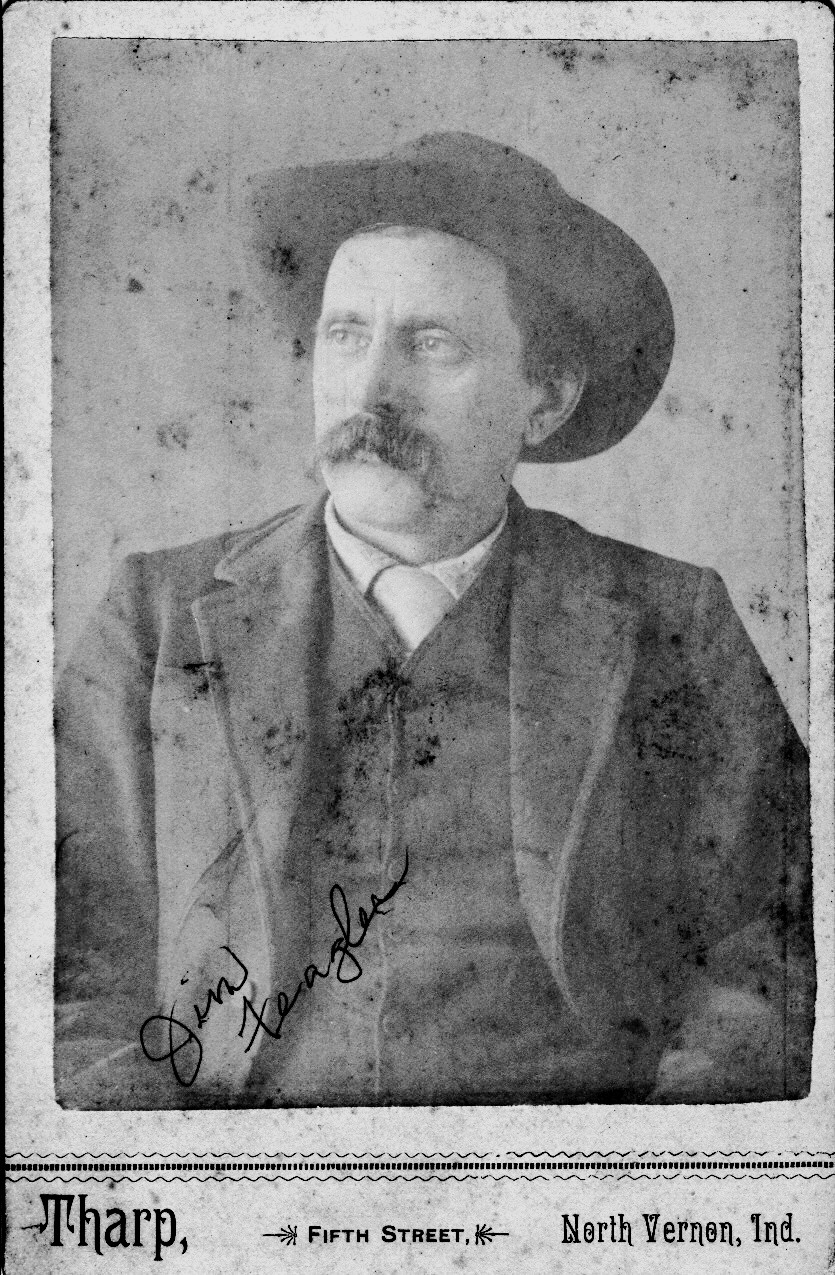

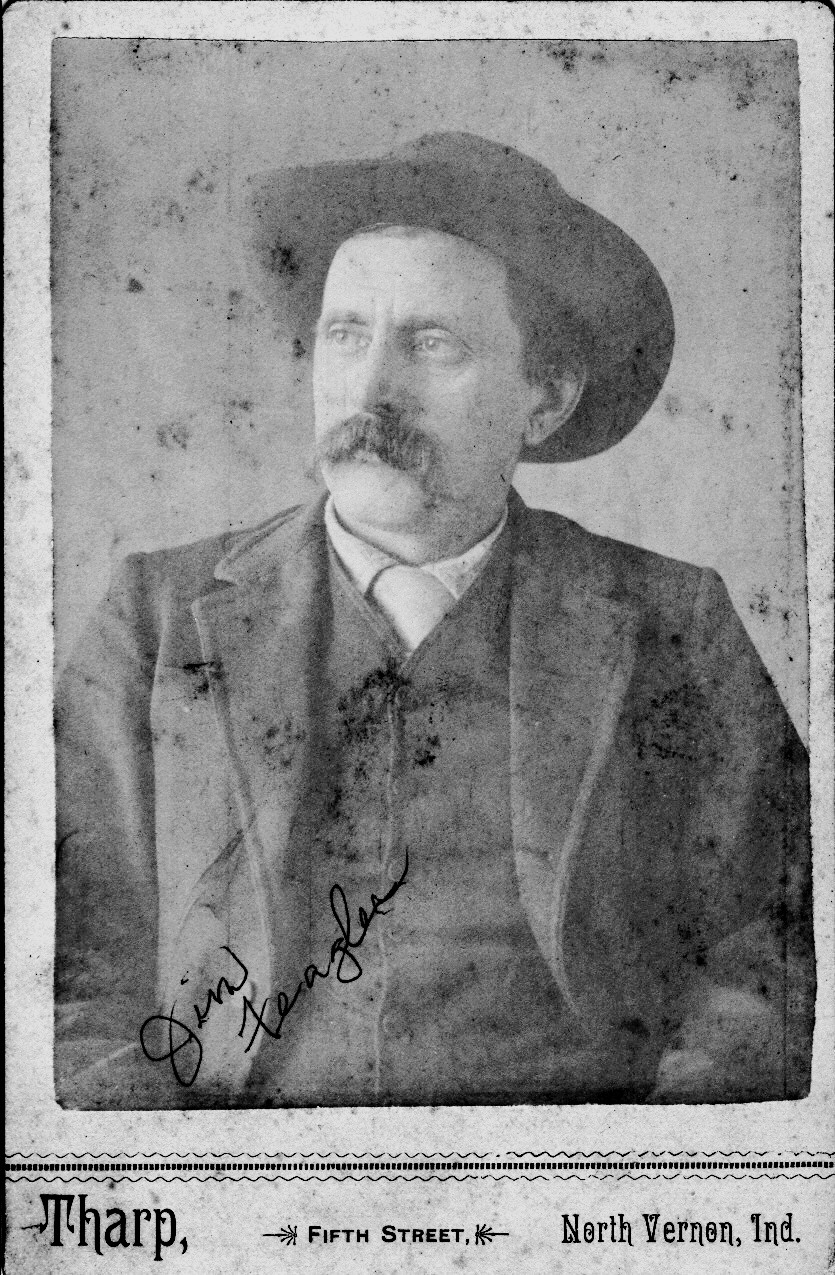

by James W. Feagler

"

Picture contributed by John & Bonnie McFarland, John is a descentant of Vawter John Feagler who was a brother of James Feagler.

Picture contributed by John & Bonnie McFarland, John is a descentant of Vawter John Feagler who was a brother of James Feagler.

You may use this material for your own personal research, however it may not be used for commercial publications without express written consent of the contributor, INGenWeb, and