The Northern Indiana Orphan’s Home

Of La Porte, Indiana

(Condensed from The Children’s Homes, Orphanages and Training Schools

of Julia A. Work by Donna M. Nelson)

In the 19th century disease, desertion, and poverty were the three primary sources of dependent children. By the 1850’s, the need for a system to care for these children was already apparent. Some of the first orphanages appeared in large cities such as Chicago in response to the cholera epidemic of 1849. According to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, parents on their way west were known to abandon their children on the streets of Chicago and, in 1853, a Cook County Grand Jury complained that the women and children's section of the county poorhouse was “so crowded as to be very offensive.” City leaders responded by building institutions for dependent children.

Many “orphans” in the nineteenth-century had one parent living. The orphanages were places that single-parent families in financial crisis could safely keep their children. Children were frequently removed from their parents’ control by Supervisors of the Poor, the early equivalent of today’s child welfare agencies.

Institutions, many privately owned, were aimed at keeping poor children from mixing either with adults in the county poorhouse or with delinquent children in reformatories or jails. Larger cities created specialized institutions for abandoned infants, while others housed all children under12 years of age. Industrial schools were founded for children between 11 and 16. A cross between orphanages and training schools, industrial schools tried to teach adolescents some sort of marketable skill.

Julia A. (Edwards) was the superintendent of a children’s home in Mishawaka, Indiana from June 1882 to February 1891, at which time Articles of Association were drawn up, establishing The Northern Indiana Orphans’ Home, to be located “at or near” the City of La Porte. The object of the association was to establish and maintain an asylum, or home, for the care, support, discipline and education of orphans and destitute children. It was to be managed by a Board of Trustees, to be elected annually, but the articles allowed for delegation of authority to the Superintendent of the Home.

The newspaper accounts of the day reflect quite a feud between the representatives of the Mishawaka Home and those in La Porte. Until Julia submitted her resignation on February 28th, 1891, the Trustees in Mishawaka were unaware of the activities in La Porte. After Julia’s defection to La Porte, a concerted and successful effort was made to convince the counties which housed their dependant children in Mishawaka to sign contracts with La Porte instead.

Reasons sited by Mrs. Work for her departure from the Mishawaka Home included claims that the buildings were rented and were in inconvenient locations and that her requests for permanent quarters were denied. She also felt that it was through her efforts that the Home was so successful and that the Society Ladies (Mrs. Studebaker was President of the Orphan’s Home) sought all of the glory for her work.

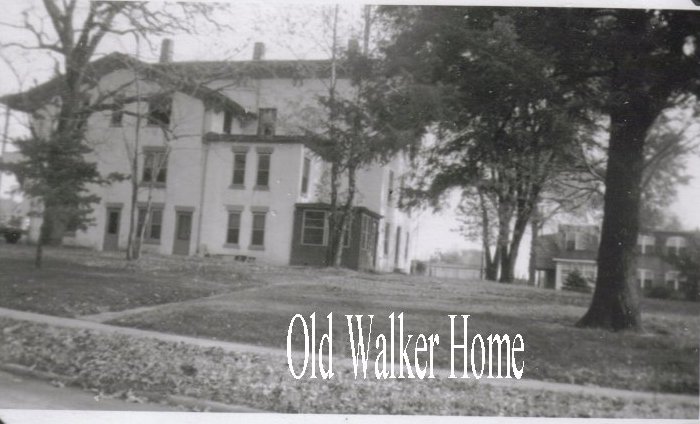

A group of 16 prominent La Porte citizens purchased a large home, originally known as the Walker Mansion and later owned by the Decker family. The building was rented to Julia Work for $480 per year. The Home was a private enterprise; she received no salary; instead, she took all receipts, paid expenses, and any remaining balance was hers to keep. Like any other business, the larger it grew, the more profit there was in it. The physical description given of the building was that it was a large, 2 story brick mansion with a basement. It had large rooms, high ceilings, water and gas. There were 9 ½ acres of land with an orchard and abundant pasture for a cow and horse. It was also located near the railroad station, which was the primary source of transportation for arriving and departing children. The railroad corporations liberally discounted rates for transporting children to and from the orphanage. A separate building was used as a hospital and isolated children with contagious diseases.

A reception heralded the grand opening of the Northern Indiana Orphans Home on March 18, 1891. A shuttle picked up loads of visitors from the corner of Main and Michigan and delivered them to the event. It is reported that hundreds of citizens and state representatives, county commissioners, township trustees, county auditors and many others visited from numerous Northern Indiana counties and were well impressed with the facility.

Although a private enterprise, donations of goods and money were aggressively sought from the public. The Daily Herald’s “Orphan News” regularly solicited donations and acknowledged those given. The citizens of La Porte were praised for their generosity. The La Porte Argus issue of December 10, 1891 carried an open invitation from County Superintendent O.L. Galbreth to the county’s school children, soliciting donations of clothing, shoes, mittens, socks, underwear, fabrics, bedding, table linens and produce. Also requested were Christmas gifts for the orphans.

Parents and friends of the children were allowed to visit on the first Friday of each month. Local residents desiring to inspect the Home and see the children could visit on Tuesdays and Thursdays. County officials and other caretakers of the poor, who wished to conduct business with the superintendent (Julia), would be seen weekdays from 9 to 4.

Between March, 1891 and 1893 the home had received 229 children and had placed 146. Initially, there were about 12 counties which contracted with Julia to care for children. The terms of the contracts varied by county; some sent only able-bodied children while others sent all of the county’s dependant children. In cases where mentally handicapped children were received, they were paid for by the counties sending them, and then were immediately taken to state institutions, frequently the Fort Wayne Institute for Feeble-Minded Children.

Homes for orphans were found principally in states west of the Mississippi river, by agents acting for Julia. The agents found homes for children, placed orders, and were paid a commission for their services. Individuals ordering a child completed an application and were expected to furnish recommendations signed by three responsible citizens. In 1899, while Indiana was sending its children to homes in Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska and the surrounding areas, the Indiana State Board of Charities estimated that in the 40 preceding years (1859-1899), between 7,000 and 8,000 dependant children from cities such as New York, Boston, Cincinnati and Chicago had been placed in the homes of Indiana families. One of Julia Work’s theories was that children who came from less than positive influences should be cut off from those influences. Therefore, she sought to permanently remove such children from their birth families and the vicinities in which they were born; thus, her reasoning for concentrating on the western states for foster and adoptive homes.

In 1897, the Indiana State Legislature passed laws which would reduce the number of children sent to orphans’ homes, by making provisions for their maintenance in other ways. It further placed a maximum of .25 cents per diem, and forbid individual counties from agreeing to contracts to pay higher amounts. As a result of these state mandated changes, the population at the La Porte home fell to an average of 30 children by mid-June, 1898. It was estimated that a population of 50 was required to avoid operating at a loss.

In June, 1898, the Plymouth Democrat reported that Mrs. Work was taking preliminary steps to organize an orphans’ home at Plymouth, thus giving the impression that she would leave La Porte. As a result, the Herald interviewed Julia, at which time she stated that, unless certain provisions were made with reference to increasing the income of the Home in La Porte, it would be necessary for her to relocate. She stated, however, that she “had no intention of leaving La Porte at present.” Two months later, in August, it was reported that she had accepted plans and specifications for changes to her Plymouth property for the purpose of relocating the children there.

There are conflicting reasons given for the relocation of the home from La Porte to Plymouth. One of those reasons is as stated above, another is that Julia wished to purchase the La Porte home and was denied. A third sited a report that she had sent the children to work for businesses and had kept the wages paid to them.

Unlike the La Porte Home, which was organized to care for dependant children, the Plymouth facility, The Julia E. Work Training School, also known as Brightside, was organized for the purpose of maintaining incorrigible and dependent children. In late January, 1899, the relocation commenced with the move of about 65 children from La Porte to Plymouth. Reports indicate the move was accomplished during an especially cold period which saw temperatures fall to 30 degrees below zero. The children were loaded into horse drawn wagons for what must have been an extremely long and uncomfortable journey. On the first night in the new home, it was discovered that the bundles containing the bedding and night clothes had been left in La Porte. The Marshall County Independent, in its issue of February 3, 1899 tells about the move and stated that many of the children were sick.

There were some allegations of abuse and neglect at the Mishawaka and La Porte institutions under the supervision of Mrs. Work, but after the relocation to Plymouth such charges became commonplace. In spite of numerous complaints, Julia continued to operate in Plymouth until 1919, when she was replaced by Mrs. Neligh, who had previously been matron of the Indiana Training School for Girls in Indianapolis.

In August, 1919 Mrs. Work moved to Malibu, California with her son Dell and his family. She died in Los Angeles on January 9, 1932. She was cremated and her ashes were returned to Plymouth, for burial at Oak Hill Cemetery.

There were no records left behind which provide names of the hundreds of children who passed through the institutions mentioned in this article. Census records provide a snapshot of residents at a given point in time, but provide names of relatively few individuals and do not reflect the period during which the Northern Indiana Orphan’s Home operated in La Porte. News articles are being reviewed for the purpose of compiling a list of some of the children who passed through the doors of La Porte’s Orphan’s Home. One news article reports that Mrs. Work kept photo albums of children who were placed in families “out west” and she is quoted as stating, “they will, in the future, afford an excellent illustration of the history of the work we are doing”. Did the albums survive? Are they in a trunk in a dark and dusty attic? How wonderful it would be to locate these albums and to see the names and faces of the orphans who passed through La Porte in the nineteenth century.